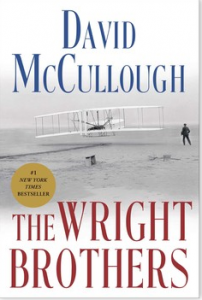

“They had had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own,” David McCullough writes in his new book about Orville and Wilbur Wright. And there was an “entirely real possibility that at some point … they could be killed.” Yet despite these long odds the Wright brothers made history – becoming the first men to fly.

“They had had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own,” David McCullough writes in his new book about Orville and Wilbur Wright. And there was an “entirely real possibility that at some point … they could be killed.” Yet despite these long odds the Wright brothers made history – becoming the first men to fly.

I liked McCullough’s detailed account of the Wright brothers’ lives. The author astutely quotes from the Wrights’ original letters and diaries to tell their story. I learned that the Wright brothers never married, and that their sister Katherine and “Bishop Wright” (their minister father) played large roles in their success. McCullough takes the reader step by step from the solitude of their first glider trials at Kitty Hawk to Wilbur’s successful motorized flight in front of thousands in France. “We couldn’t help thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts. They’d stand on the beach for hours at a time just looking at the gulls flying, soaring, dipping,” McCullough quotes a Kitty Hawk resident of those early days. In contrast, after Wilbur’s European flight, the Paris Herald reported “There were shouts of ‘C’est l’homme qui a conquis l’air!’ This man has conquered the air!”

The Wrights come across as a very ordinary American family who accomplished extraordinary things. Before Kitty Hawk, before any of the fame that would come their way, McCullough shares interesting little vignettes on the brothers’ growing up years. “Orville’s first teacher in grade school, Ida Palmer, would remember him at his desk tinkering with bits of wood,” the author writes. “Asked what he was up to, he told her he was making a machine of a kind that he and his brother were going to fly someday.” In another chapter we are told of Wilbur as a high school senior being smashed in the face while playing hockey on a frozen pond (“they played hockey in the 1880’s??” I wondered). The hockey incident derailed Wilbur’s plans to enroll at Yale. causing him to become a recluse at the Wright home for three years – a period in which he read extensively and spent more time with Orville. Had the hockey fight not happened, perhaps Wilbur would have gone on to Yale, there would be no partnership with his brother, and manned flight would have been discovered by someone else.

I was fascinated by the ups and downs Orville and Wilbur endured along their journey. “Probably not one person in a hundred believed the brothers had actually flown in their machine, or if they had, it could only have been a fluke,” McCullough writes about the initial reaction in the Wrights’ home town of Dayton. In another chapter the author tells of Orville Wright’s near fatal crash on a test flight that killed the sole passenger – the first fatality in aviation history. Even with fame the Wrights had their challenges, winning numerous law suits from others trying to steal their ideas. And I found compelling what Orville Wright said in his later years, after the horrors of World War II, of what had become of their airplane invention and its use in warfare.

The spirit of the Wrights was captured best by their father Bishop Wright, who in the last years of his life finally flew with his internationally acclaimed son Orville. Not letting fear stop him from enjoying the ride at the ripe old age of 82, the Bishop reportedly yelled to his son, “Higher, Orville, higher!” Modern day dreamers would do well to learn from the Wright brothers’ story, to persist despite setbacks and criticism to achieve their own lofty goals.

Comments

Pingback: My top 5 books of 2015 | Tim Larison